A survey of small animal first opinion practices in the UK (Hill et al, 2006) showed more than 20% of the patients seen presented with dermatological signs.

Apart from routine appointments – such as vaccinations – dermatology is, therefore, one of the major pillars of first opinion practice.

In the study, approximately 30% to 40% of the canine and feline patients with dermatological issues suffered from pruritus. Cutaneous swellings were second in cats, affecting 36% of skin patients.

This shows how important a working knowledge in small animal dermatology is for the general practitioner.

The scope of this paper does not allow for a very detailed discussion of all the minute details in the diagnosis and management of all potential dermatological conditions presented to small animal practices, but concentrates on the top two diagnoses. In dogs and cats, these are parasitic infestations and bacterial infections.

Parasites

Parasites are very common in the small animal population, despite the availability of many safe and reliable products to prevent and treat infestations.

Owners are often unaware of the infestation – according to Bond et al (2007), almost half of owners of flea‑infested cats did not know their pet carried fleas.

The most important parasites are fleas, Sarcoptes scabiei and Cheyletiella species. They all present with a clinically very distinct lesion distribution.

Fleas

Fleas are not picky. They can infest several host species – for example, the cat flea is commonly found on dogs. They multiply very quickly and are, therefore, a very successful genus.

In addition to causing pruritus due to their mere presence; being the vector for several diseases, including Bartonella and Rickettsia species (Barrs et al, 2010); transmitting Dipylidium caninum; and, in heavy infestation, being able to cause anaemia, flea bites can induce an allergy to antigens in flea saliva – flea allergy dermatitis (FAD).

The latter is the condition for which owners more often present their pets – cats in particular – in contrast to an infestation without allergy, which most owners do not notice.

In susceptible animals, the development of FAD is promoted by intermittent exposure to fleas (Columbini et al, 2001), which often occurs in pets treated with flea preventives on and off, rather than continuously.

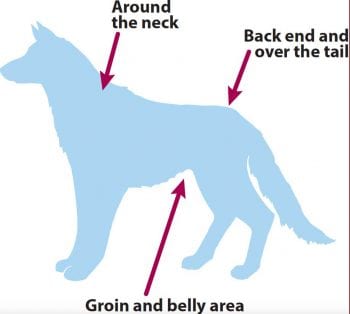

Flea allergy in the dog is characterised by a distinct lesion distribution (Figure 1) affecting mainly the caudal dorsum or the “Bermuda Triangle” of fleas. The condition can be exquisitely pruritic, often causing profound pruritus and self‑traumatic crusting, alopecia and secondary pyoderma.

Once an animal has become sensitised to fleas and allergy, only a few flea bites can lead to a cycle of allergic inflammation, pruritus, self‑trauma and deterioration through secondary infection that can lead to very severe clinical signs.

The individual threshold or number of flea bites that start the vicious cycle in each host animal varies a lot between individuals. Flea allergy in the cat leads to military dermatitis more commonly, but any of the feline cutaneous reaction patterns can be caused by FAD.

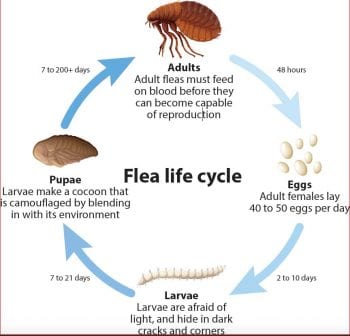

Good flea control requires knowledge of the flea life cycle (Figure 2) and it is important to educate owners to this effect.

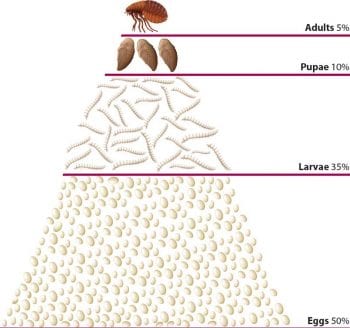

Only a small minority of the total number of flea life stages are adult fleas on the host animal. The vast majority are flea eggs, larvae and cocoons in the environment, mostly the house (Figure 3).

To achieve good flea control, some kind of environmental control is, therefore, necessary unless the adult fleas on the host can be killed before they are able to lay eggs, which they start doing within 24 hours from infesting the host.

In effect, this means either a combination of a long‑acting adulticide on the host with a long-acting insect growth regulator/adulticide combination in the environment, or a product with a fast knock‑down time.

A host of suitable products are available.

S scabiei

Sarcoptic mange, or fox mange, is usually an intensely pruritic and highly contagious condition of foxes, dogs and ferrets. It is also zoonotic.

Sarcoptic mange also has a very characteristic lesion distribution. Affected areas include the ear margins, elbows and hocks.

Diagnosis is made in dogs with a compatible history (often with relatively acute‑onset, intense pruritus and sometimes a history of in‑contact animals or the owners also being affected) and clinical signs (characteristic lesion distribution) with a skin scraping, serum IgG testing, pinnal-pedal reflex or trial therapy with a suitable product licensed for this parasite.

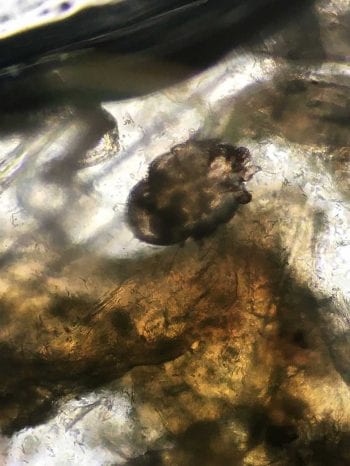

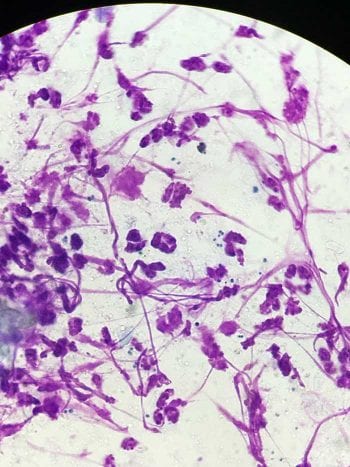

The different diagnostic methods show a very different sensitivity and specificity, and this needs to be kept in mind. A good skin scrape, carried out by an experienced clinician, has still got a relatively low sensitivity as very few mites (Figure 4) can cause intense pruritus in some animals and they may be very difficult to find. However, the specificity is very high.

To increase the sensitivity, several skin scrapings should be carried out and a relatively large area should be sampled. Liquid paraffin is used for the scraping and collected on to a slide. Ideally, the sample should be carefully examined in‑house to obtain an instant answer.

Serum IgG testing has got a much higher sensitivity and good specificity (both mid-90s%). However, it takes a bit longer to obtain and answer, and the cost may be higher. If skin scrapings are negative and the suspicion is high, it is a worthwhile test.

The pinnal-pedal reflex entails stimulating the rim of the pinnae digitally – if it is positive, a scratch response of the dog with the ipsilateral hindlimb can be elicited.

Again, sensitivity and specificity are said to be relatively high. However, other conditions affecting the ear margin can also lead to this response.

As it is an easy and non‑invasive test, it is good practice to carry it out despite the reservations.

Trial therapy is indicated for all cases where a suspicion of sarcoptic mange exists, despite negative laboratory testing. A suitable product is used and response to therapy observed.

It is important to realise that the time to respond varies significantly between patients. This is an indicator that pruritus does not just depend on infestation with the mite, but also largely on the response of the host’s immune system. This also explains why, if several dogs are in the household, one shows severe clinical signs and others are seemingly unaffected.

Nonetheless, it is important to treat all in-contact animals, as they are most certainly silent carriers. Again, nowadays many suitable, easy‑to‑use and licensed products are available.

A secondary infection is commonly associated with this parasitic infestation, and needs to be identified, ideally cytologically and treated accordingly. An antibacterial shampoo is a good solution as it can treat the secondary infection, and remove the dead mites and their faeces that elicit a hypersensitivity reaction leading to increased pruritus.

In confirmed cases – or if a very strong suspicion of this condition exists – antipruritic therapy is warranted for welfare consideration, as it is so intensely pruritic in many cases. This is particularly important in view of many cases initially deteriorating when miticidal therapy is initiated, probably as the dying mites defecate, thereby delivering more allergenic substances.

Cheyletiella species

Cheyletiella species are seen less frequently nowadays, due to so many effective ectoparasite preventives available and being used; however, in untreated animals they still occur.

Again, in the dog, classical clinical signs and a characteristic lesion distribution exist – most patients affected with Cheyletiella mites usually suffer from predominantly dorsal pruritus and scaling. The mites are not called “walking dandruff” for no reason.

Diagnosis of this contagious and zoonotic, pruritic dermatosis is made due to a classical history, characteristic lesion distribution and clinical signs, as well as positive laboratory testing.

The easiest method to find the mites is probably the tape strip method, for which clear sticky tape is repeatedly applied to the dorsum to collect the typical scales and, hopefully, mites. The tape is then stuck on to a microscopic slide and examined microscopically under low power. A coat brushing or skin scraping are also good methods to detect the mites.

Again, the sensitivity is not 100%, so trial therapy is warranted in suspicious cases.

Many modern flea products are also efficacious – and some licensed – for Cheyletiella species. Again, in‑contact animals must be treated. Different species of Cheyletiella mites exist, which affect dogs, cats and rabbits, and are zoonotic.

Bacterial skin infections

Bacterial skin infections, or bacterial pyoderma, are a common occurrence secondary to other skin condition.

They are commonly seen as a secondary phenomenon in animals suffering from ectoparasite infestations, allergic skin disease, endocrinopathies and other primary diseases.

Bacterial skin infections occur more commonly in dogs compared to cats, in part possibly due to the fact their follicular ostia are much wider and open, giving access to bacteria more readily and many other factors.

Organisms implicated are usually staphylococci; in the dog most commonly Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. They are a normal part of the resident flora, and get a chance to overgrow and become more abundant when something goes wrong; pyoderma occurs as a result.

In these vicious cases, it is most important to diagnose and adequately treat the underlying disease; otherwise, a cycle of symptomatic therapy, remission, relapse and repeated symptomatic therapy occurs.

Before the diagnosis of bacterial pyoderma is made in the first place, the presence of bacteria must be demonstrated – ideally by performing cytology (Figure 5), either in-house or sent to a commercial laboratory. In recurrent cases, it is prudent to perform culture and sensitivity testing.

In the interest of antibiotic stewardship, antibiotic therapy should be avoided, if at all possible, and suitable topical alternatives sought. In most cases, particularly if focal superficial pyoderma is concerned, this is very doable. Many shampoos with chlorhexidine are available and other formulations – including sprays, foams, gels and wipes – exist that are very easy to use, if needed daily, and can be an adjunct to the less frequent use of a shampoo (which is more time‑consuming).

Topical therapy is also preferable in cases of multiresistant bacteria and can achieve very good results if used diligently.

The search for the underlying disease must occur in parallel to avoid the cycle of therapy and relapse as aforementioned. Most of these patients – particularly if the problem occurs in young adult pets – suffer from an allergy, and require a thorough work‑up and lifelong management.

Approach in first opinion practice

Due to the complex nature of skin disease in pets, with many conditions looking very similar at first glance, it is important to spend some time investigating further than just prescribing symptomatic therapy – particularly in chronic cases.

Ideally, a thorough history should be taken, which often gives important clues as to the underlying primary disease. A general physical – as well as specific dermatological – examination should be performed. All the information can then be used to formulate a ranked list of differential diagnoses, and, from this list, follows an initial diagnostic and therapeutic plan.

In-house tests, such as cytology and skin scrapings, are helpful in the vast majority of cases, both for a first consult and follow-up consultation. In some cases, a final diagnosis can be made based on these tests, or the diagnostic and therapeutic plan improved based on the results.

Check-up consultations are needed for most cases to follow therapeutic response and eventually make a final diagnosis. Most dermatological conditions are lifelong diseases and require life-long management. Only once a diagnosis has been made can specific therapy be prescribed.

As the process of history taking, examination and owner education can be quite time‑consuming, your average duration in first opinion practice is often not sufficient. Clever solutions must be sought – such as booking longer appointments, splitting the process into a series of consultations, putting the emphasis on different aspects for each session, using your valuable nursing staff (possibly after some further training), using questionnaires, taking samples during the consult, and examining patients later and calling owners with the result and therapeutic plan.

Some cases benefit from referral if they continue to defy a diagnosis or successful management plan.

from Vet Times

0 Comments